Lessons from the Yelwata Massacre...

By edentu OROSO

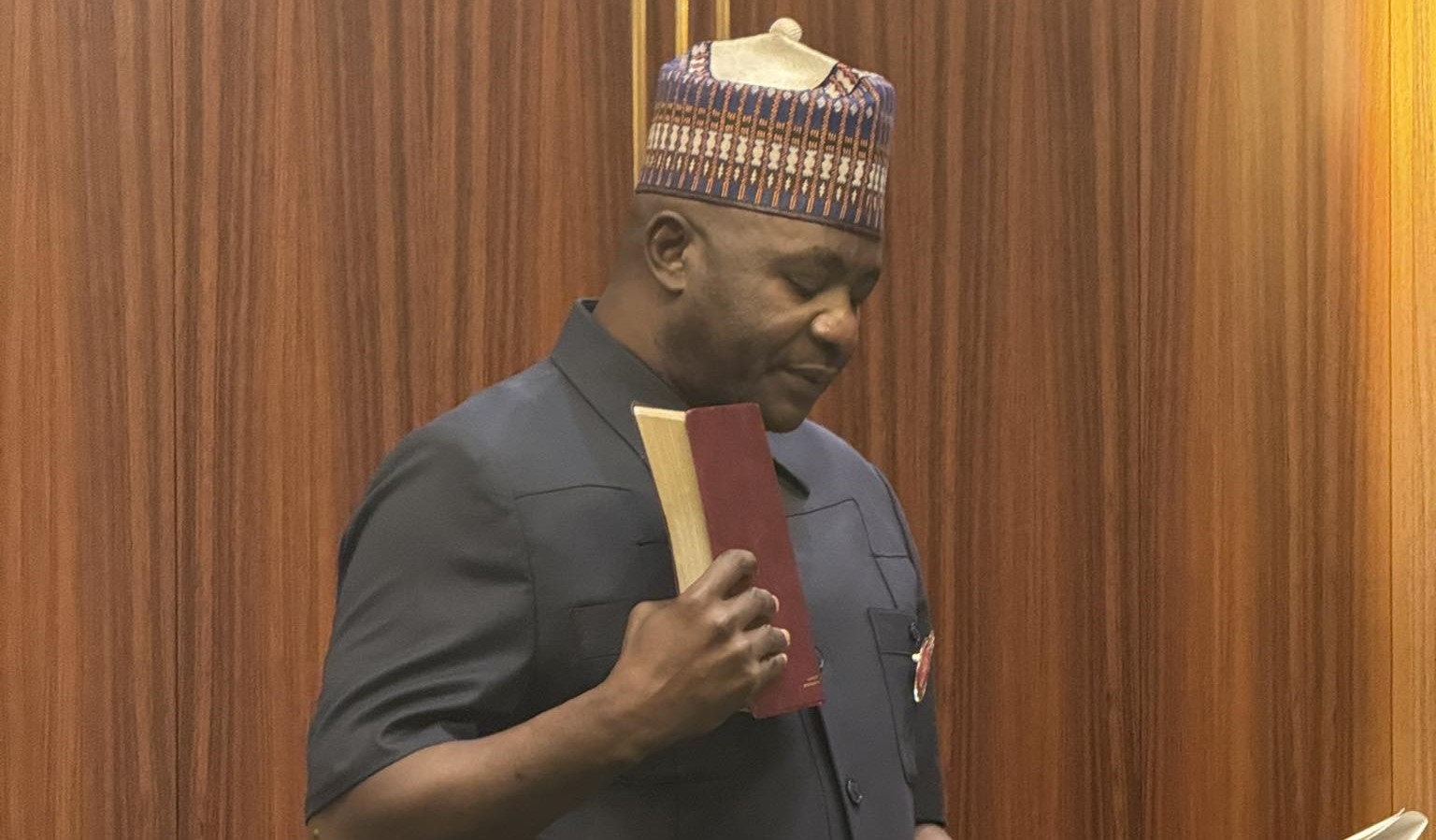

President Bola Tinubu

President Bola Tinubu

There are myriad lessons to be drawn from President Bola Tinubu’s visit to Benue State in the aftermath of the Yelwata killings. First, it provided the political class ample runway to soar unchallenged on the emotional tides of the tragedy, pushing thinly veiled agendas beneath the guise of national concern. Second, the very citizens who bear the heaviest burden of Nigeria’s national security failures, the ordinary people, unwittingly compounded the charade by failing to read the national mood at such a dire moment of cold-blooded slaughter.

In sum, the convergence in Makurdi of the political elite and swathes of grief-stricken Benue indigenes, who hoped for genuine solace from the President, devolved into a carnival of hollow rhetoric, tone-deaf speeches, and a carefully orchestrated rebuke of the governor’s political innocence in Nigeria’s treacherous arena of power play. It is hardly surprising that it took President Tinubu five days to decide on the visit, something that, in saner societies, would have occurred almost instinctively. That delay alone underscores the lack of urgency.

The visit reeked of afterthought, more a product of political recalibration than a heartfelt response to a state in trauma. Layered beneath the public optics were subtle barbs, veiled warnings, and a strategic attempt to mold the governor into a more compliant figure in the unfolding political script aimed at 2027, one riddled with roadblocks, shifting loyalties, and Benue’s pivotal role.

The President’s body language spoke volumes, betraying a sense of urgency laced with political calculation. His public scolding, or, if one prefers, the tutelage of the Reverend governor, still green in the dark arts of power, came wrapped in a passive-aggressive narrative. Blame was subtly redirected under the guise of “reprisal attacks” and “neighbourly disharmony,” euphemisms that mask the long-standing reality of herders’ aggressive land incursions against peasant farmers in the Benue Valley.

Third, and perhaps most damning, was the President’s failure to visit Yelwata itself, the actual site of the massacre. That omission alone, in a region desperate for healing, stripped the visit of whatever symbolic balm it might have offered to a wounded people. In any truly civilised society, no leader visits the scene of mayhem, be it natural or man-made, based solely on distant impressions or filtered reports. Such pilgrimages are anchored in

empathy, meant to reassure a grieving people that they are seen, heard, and not abandoned.

But this was not the spirit that underpinned President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s visit. In choosing to avert his gaze from the gruesome aftermath of the mass slaughter, where over 200 souls in Yelwata perished, he squandered a profound, perhaps historic, opportunity to inscribe his name not just in the heart of that tormented community, but in the soul of the Tiv nation.

Security briefings, no matter how sanitised, should never eclipse the raw truth on the ground, nor

should they dampen the urgency of human compassion. What added insult to injury was the theatrical absurdity that accompanied the visit: schoolchildren lined along the roads, singing orchestrated praise songs; a carnival of banners and placards; the shrill parade of loyalists choreographed more for the optics of 2027 politicking than

the solemnity of mourning. From the Makurdi airport tarmac to the venue of empty rhetoric, it was a spectacle that reeked of misplaced priorities.

By every conceivable metric, the undisputed star of the moment was none other than His Royal Majesty, Begha U Tiv, Orchivirigh, Professor James Ortese Iorzua Ayatse, Chairman Benue State Traditional Rulers Council. His bold, clear-eyed appraisal of the enduring plight of a people edging dangerously close to extinction was nothing short of statesmanlike. In a time of national crisis, true leadership demands the courage to name things for what they are—and the Tor Tiv did just that. He left no room for ambiguity, declaring in unmistakable terms that what confronts the Benue people is not a reprisal of any kind, but a deliberate, coordinated campaign, a marshal

plan, for land seizure and displacement.

This tragedy, sadly, is no longer Benue’s burden alone. It is metastasising into a national affliction, playing out in various forms across the country: in the unending clashes between herders and farmers, and in the simmering settler-indigene conflicts that have become an all-too- familiar refrain. During the visit, President Bola Tinubu made a number of significant remarks. Chief among them was his call on Governor Hyacinth Iormem Alia to convene a think tank, one inclusive of traditional leaders, past governors, and critical stakeholders such as the Secretary to the Government of the Federation.

This proposed parley in Abuja, ostensibly aimed at crafting a path forward, is welcome in principle. Yet it bears the markings of a well-worn ritual, an echo of the bureaucratic merry-go-round that often substitutes motion for meaning in the Nigerian polity. What the Yelwata massacre and other tragedies across Nigeria demand is not another round of ponderous consultations. They demand swift, decisive, and protective action, interventions that

save lives and secure communities. We have danced this dance before. The time for endless dialogue is past. What is needed now is resolve.

The President’s suggestion that Governor Alia should take a cue from his peers, those who, through strategic alliances and shared intelligence, have managed inherited crises with relative success, may, on the surface, seem like sage counsel. His reference to his own tenure as governor of Lagos State, and the deftness with which he navigated periods of unrest, lends weight to the advice. Yet, such comparisons falter in the face of the grim reality confronting Benue. This is not a crisis of misgovernance or administrative inertia, it is the slow burn of a war declared on an entire people.

The President’s proposal for the establishment of ranches in Benue may, on the surface, offer a compelling solution, if implemented to the letter. Yet, one must ask: do the Fulani herders, whose traditions are steeped in nomadism, truly subscribe to the sedentary discipline of ranching? When the pulse of their identity beats with the rhythm of open skies and untamed paths, from the savannahs of the north to the forests of the south, is it realistic to expect them to abandon the liberty of movement for fenced pastures? Their age-old impulse is not to settle, but to roam, to conquer where the terrain allows, and to assert presence wherever pasture beckons.

Benue State must draw inspiration from regional security outfits such as Amotekun in the Southwest and the Eastern Security Network (ESN) in the Southeast, as a necessary complement to whatever protection the federal government can offer her people and land. The state can harness President Bola Tinubu’s Forest Guards initiative or activate state-recognised vigilante groups to safeguard its expanse from the mounting carnage spreading across its vast terrain.

Sole reliance on the armed forces and the police may no longer be viable, given the dire straits in which the nation currently finds itself. As General Theophilus Danjuma recently warned, self-help may well be the only recourse in the face of the barbaric massacres witnessed in Yelwata and other parts of Benue—and beyond.

Comments

Be the first to comment on this post

Leave a Reply