Political Appointments and the Nigerian Reality...

By abidemi ADEBAMIWA

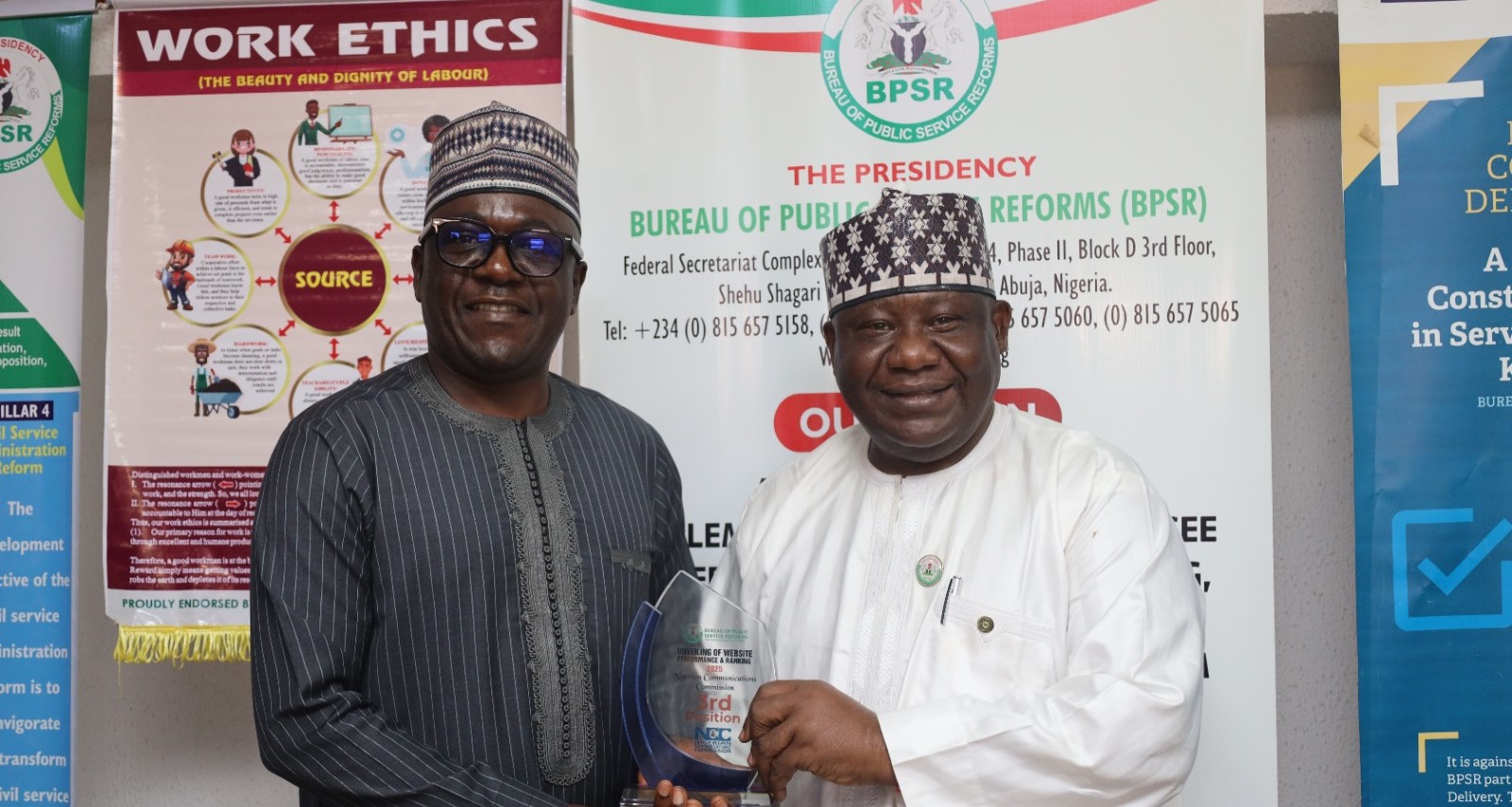

Muhammad Babangida recently appointed Chairman, Bank of Agriculture by President Bola Tinubu

Muhammad Babangida recently appointed Chairman, Bank of Agriculture by President Bola Tinubu

We all see it. Elections come and go, but one thing never changes—once the votes are counted, the appointments begin. Not just any appointments. These are calculated, deliberate, and often predictable. It’s not about who’s best for the job. It’s about who delivered. Who promised votes. Who can still pull a crowd.

Across the country, the conversation is no longer about qualifications. It’s about compensation. You hear it in hushed meetings and open rallies—“our zone must get a slot,” “we deserve something at the center.” Appointments have become bargaining chips in a game that’s less about governance and more about settling political IOUs.

Even before elections, the trades begin. A region is offered a plum federal slot in exchange for votes. A key political actor is promised a board chairmanship if he can deliver his district. It's subtle, sometimes coded, but everyone understands the deal. It’s no longer public service. It’s campaign strategy with the seal of office.

The recent statement by the African Democratic Congress (ADC) shows how clearly this reality is being noticed—and challenged. The party accused President Tinubu of using a new wave of federal appointments not as a step toward national inclusion, but as a desperate move to regain the trust of Northern Nigerians after what it called “over two years of neglect.”

“You cannot marginalise a region for over twenty-five months and expect applause because you suddenly remembered on the twenty-sixth month that Nigeria is bigger than Lagos State,” the ADC said through its National Publicity Secretary, Bolaji Abdullahi. To many Nigerians, that statement cut deep, not because it was new, but because it felt familiar.

ADC called the move “political panic management,” not policy leadership. And whether one agrees or not, the core question remains: when appointments are rolled out as consolation prizes, are we still governing—or just pacifying?

The EFCC says it’s currently investigating 18 sitting governors. That’s progress. It shows that some boundaries are finally being challenged—that the shield of office is not as bulletproof as it once was. For a country weary of watching public officials enjoy unchecked power, it’s a sign of movement, however small.

But let’s not get carried away.

The probe of governors—welcome as it may be—will ring hollow if we ignore what happens before the looting. When appointments themselves are political rewards in disguise, the rot doesn’t begin with the money that goes missing. It begins the moment a person is handed power, not because they’re capable, but because they’re loyal. Or useful. Or available for trade.

The case of former Plateau State Governor Joshua Dariye is a stark reminder. EFCC testimony detailed how he allegedly diverted ?1.126bn in ecological funds by personally collecting the cheque and instructing how it should be shared—some to political associates, others to unregistered shell firms. One payment of ?100m was traced to “PDP South-West,” and ?250m was linked to a private contractor. A Permanent Secretary collected ?80m and fled the country after charges were filed. It all started with how Dariye controlled appointments and built a circle of loyalty—public office turned into personal cover.

And it’s not just Nigeria. In South Korea, President Park Geun-hye was forced to resign from office after it was revealed that her close associate, Choi Soon-sil—who held no official position—was secretly influencing appointments, editing presidential speeches, and using her connections to solicit ?77.4bn (approximately $60 million) from major corporations. The backlash sparked mass protests, global headlines, and Park’s impeachment. She was eventually sentenced to 25 years in prison.

That was not an isolated case. Brazil’s Michel Temer was arrested for using public appointments to secure political loyalty and conceal corruption. In the U.S., Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich was caught trying to sell a Senate seat and was jailed. In Nigeria, just like Governor Joshua Dariye, former Taraba Governor Jolly Nyame was convicted not just for theft, but for weaponizing appointments to enable it.

These aren’t random scandals. They are warnings.

Appointments are not neutral. They shape everything—budgets, contracts, influence. And when they’re handed out like political favors, the nation bleeds slowly from the inside. Ministries become reward centers. Agencies lose their backbone. And merit is the first casualty.

Perhaps that’s why our institutions are struggling. Why performance is inconsistent. Why innovation struggles to survive. The people best suited to lead are often the ones most excluded, because they didn’t shout the loudest during primaries or weren’t owed anything.

Nobody is saying a leader shouldn’t work with trusted hands. But trust must be earned through service, not sealed in a smoky hotel room after campaign rallies. Every appointment is a message. It tells the country what we value. If we keep valuing loyalty over competence, we shouldn’t pretend to be shocked when failure repeats itself.

The EFCC can probe all it wants. Until we start scrutinizing how people rise into office—what their appointments are really for—we’ll keep chasing the fruit while ignoring the root.

Public office is not a thank-you card. It’s a responsibility. And until we treat it that way, nothing truly changes.

Comments

Be the first to comment on this post

Leave a Reply