The AI Revolution and Future of Education

By edentu OROSO

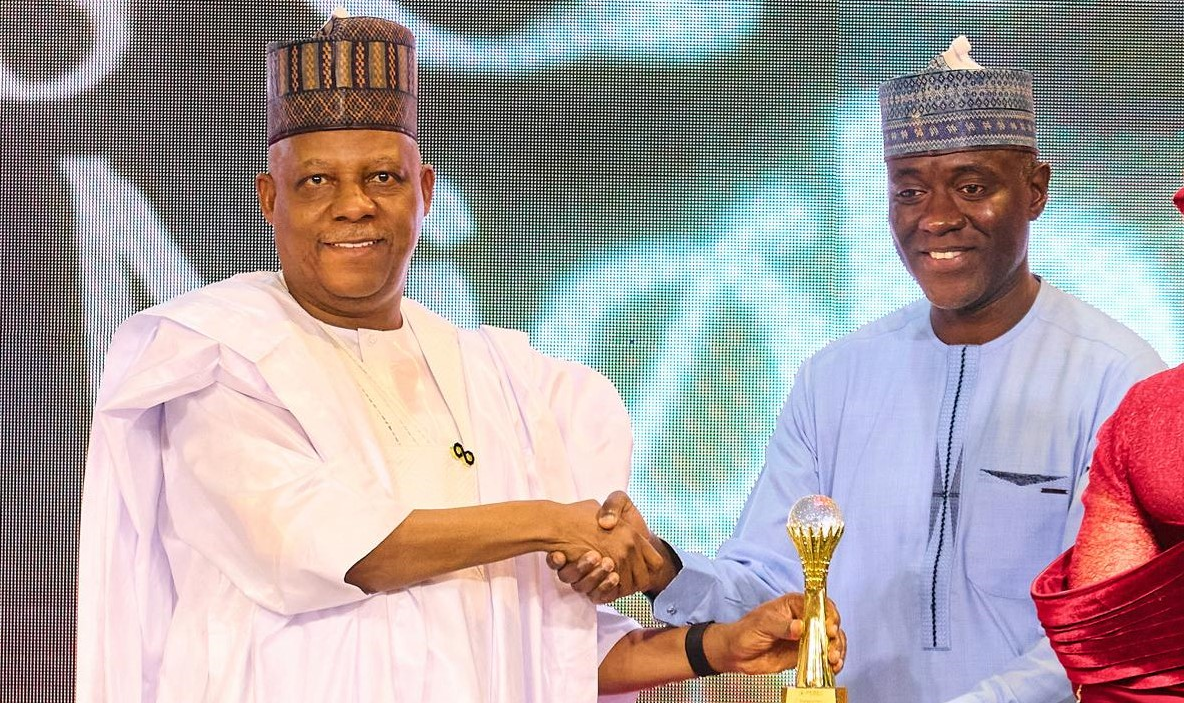

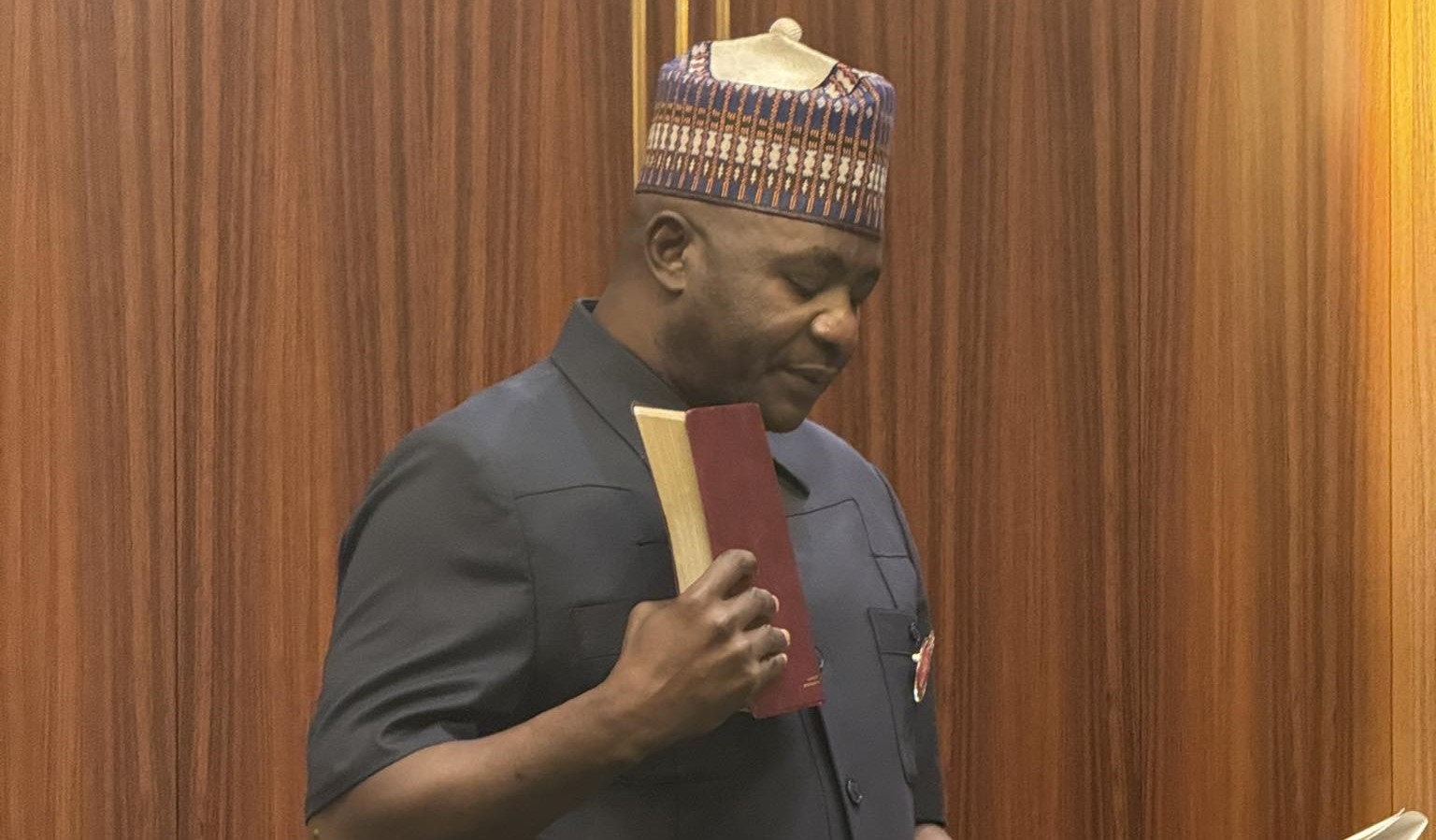

Minister of Education, Tunji Alausa and Provost of University of Birmingham, Stephen Jarvis forging Global Future

Minister of Education, Tunji Alausa and Provost of University of Birmingham, Stephen Jarvis forging Global Future

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is in full motion, powered by technologies that are redefining how we work, communicate, and learn. At the forefront of this revolution is Artificial Intelligence (AI)—no longer a futuristic concept relegated to science fiction but a transformative force reshaping everyday life. Education, perhaps more than any other sector, stands at a critical crossroads: adapt or become obsolete.

AI is already demonstrating its disruptive power in the education sector. From intelligent tutoring systems to AI-driven grading software, voice assistants, plagiarism detectors, and learning analytics dashboards, institutions are leveraging intelligent systems to enhance efficiency, deepen engagement, and personalise learning. These tools promise a democratisation of knowledge, enabling learners to access tailored content regardless of geography or background.

Yet, as the tide of AI rises, it brings not only potential but peril.

But isn’t personalised learning a double-edged sword?

One of AI's most celebrated contributions to education is its ability to personalise the learning experience. Intelligent algorithms can monitor a student's performance in real time, adapting lessons to their strengths and weaknesses. Platforms like Carnegie Learning and Squirrel AI in China use data-driven diagnostics to tailor instruction, allowing struggling students to revisit concepts while fast learners move ahead.

This individualisation is especially valuable in large classrooms where one teacher may struggle to meet diverse learning needs. With AI, students no longer have to conform to the pace of the curriculum; the curriculum adapts to them.

However, there’s a caveat. Hyper-personalisation risks creating intellectual echo chambers. If AI systems continuously feed learners content based solely on their past behaviour, it may limit their exposure to new ideas and diverse perspectives. Education must not become an algorithmic bubble. Curiosity thrives on unpredictability—and while AI is excellent at optimising efficiency, it must not come at the expense of intellectual exploration.

Despite the optimism, AI’s promise remains out of reach for millions of learners, particularly in low-income and remote regions. While elite schools experiment with AI-powered labs and classrooms, many rural and underserved schools struggle with electricity, internet access, and even basic teaching materials.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where teacher-student ratios can exceed 1:100, AI could be revolutionary—but only if the infrastructure exists. Without conscious policy interventions, the AI revolution may reinforce existing inequalities rather than resolve them. Ensuring equitable access requires not only connectivity but also affordability. Open-source AI platforms and low-bandwidth applications will be crucial to bringing smart learning to the global South.

AI will not replace teachers, but it will redefine their role. Rather than being the sole source of information, teachers must evolve into facilitators, mentors, and designers of learning experiences. AI can handle administrative drudgery—grading assignments, monitoring attendance, or providing instant feedback—freeing up educators to focus on emotional intelligence, moral development, and critical thinking.

But are teachers ready? In many countries, teacher training curricula do not include modules on digital literacy, let alone AI. Many educators still view AI with suspicion, as a threat to job security rather than a collaborative tool. Bridging this gap requires a nationwide retooling of the teaching workforce—ongoing professional development, hands-on exposure to AI tools, and support systems to help educators integrate technology meaningfully into pedagogy.

AI systems in education gather vast amounts of data—academic performance, behavioural patterns, even keystroke dynamics. This data is valuable for optimising learning but also raises significant privacy concerns. Who owns this data? How is it stored, and who has access?

There have already been instances of algorithmic bias in predictive analytics used for university admissions or scholarship allocation. If left unchecked, these biases can reinforce systemic inequalities under the guise of data-driven objectivity. Ethics must become a cornerstone of AI deployment in education, with clear regulations on transparency, consent, accountability, and redress.

Few discussions on AI in education mention its environmental cost. Large-scale AI systems require enormous computational power, translating into substantial energy consumption. For instance, training a single large language model can emit as much carbon dioxide as five cars in their lifetime.

As educational institutions increasingly rely on cloud-based AI services, they must also invest in green computing practices—energy-efficient data centers, renewable energy integration, and environmentally conscious coding.

AI is not just a tool for education—it is also a subject that must be taught. Future learners must not only know how to use AI, but how it works, what its limitations are, and how to engage with it ethically. AI literacy should be woven into school curricula from an early age, just as reading, writing, and numeracy once were.

This means teaching students about algorithms, data interpretation, automation, and critical thinking. It also means fostering creativity, empathy, and collaborative skills—traits that no machine can replicate.

Some countries are already leading the way. Singapore has introduced AI ethics and literacy into its national curriculum. Finland has rolled out a nationwide AI education program that offers citizens free online courses to understand AI’s implications. These are models worth studying and adapting.

Ultimately, education is not just about content delivery. It is about growth, connection, and transformation. The best teachers do more than teach—they inspire. They notice a struggling student before an algorithm does. They nurture potential that no dataset can predict.

AI can support this human connection, but it cannot replace it. As education becomes more data-driven, we must not lose sight of its soul.

The path forward is neither about resisting change nor blindly embracing technology. It is about intentional innovation. Governments, institutions, and educators must come together to:

- Develop inclusive policies that bridge the digital divide

- Invest in teacher training and AI literacy programs

- Establish ethical frameworks and data protection laws

- Support sustainable technology use

- Rethink curricula for a world shaped by automation and augmentation

AI has the potential to make education more inclusive, efficient, and effective—but only if wielded with care, conscience, and clarity of vision.

The future of education lies not in choosing between human or machine—but in building a system where both work in harmony, each amplifying the strengths of the other. In this partnership, learners are not passive recipients but active participants—equipped to thrive in a world where learning is no longer a phase of life, but a lifelong pursuit.

Comments

Be the first to comment on this post

Leave a Reply